Texts

Brett Murray has long been one of South Africa’s sharpest, most subversive visual artists. Known for his biting wit, iconic sculptures and fearless commentary, he’s also a man of music, mischief and meticulous pool maintenance (and one of Currency’s favourite creatives too). Here, he lets us in on everything from bodyboarding to the emotional power of Nick Cave.

What’s the best book you’ve read in the past year – and why?

Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan’s Faith, Hope, and Carnage. I’m not a huge fan of Cave’s music, but I am learning. My wife Sanell is a huge fan. I booked tickets for us to see him in Madrid for Sanell’s birthday a few years ago – but then came Covid and lockdown. Fok.

I found his Red Hand Files website a few years ago. On the site he answers questions from his fans. His writing is funny, insightful and scarily honest. Often about what inspires or moves him: religion, death, spirituality. Both his sons have tragically died. He speaks so eloquently about this loss and his grief and what he calls “communal vulnerability”.

The book is in a way an extension of the Red Hand Files. It documents 40 years of his life in conversations with the critic and writer Seán O’Hagan. In his words, the book offers “ladders of hope”. Brave stuff.

One of my favourite quotes, for obvious reasons, is: “Humour is the merciful oxygen that can envelop seriousness and prevent it from becoming a grim contagion that infects ourselves and those around us. True humour is the antidote to dogmatism and fanaticism, and we must be cautious of the humourless who cannot take a joke.” Hell yeah …

How do you keep fit?

I bodyboard with my sons from time to time. It might be a midlife crisis. I play tennis every Wednesday evening in Pinelands. This transgressive stone-throwing pretend-pretend iconoclast has obviously thrown in the towel. I’m told Pinelands is the suburb where the middle classes go to die. I’m 63 so I am eyeing out the bowling club next door to the tennis courts … next to that is a church … and that is a fart away from the cemetery. It’s a slippery slope. Done then dusted …

Weeknight, low-key restaurant go-to?

Willoughby & Co – the sushi place at the V&A Waterfront. Bond the house first … but you can do some last-minute shopping for the kids’ lunch boxes and go to Exclusive Books for a quick perusal as well.

What is the one artwork you’ll always love – and why? (You needn’t own it!)

That would definitely be Claudette Schreuders’ Mother and Child. I saw this work again with my family over the weekend. It’s currently in the show titled Motherhood: Paradox and Duality at the South African National Gallery.

I met Claudette when she was in her first year at Stellenbosch. I was her lecturer. I was establishing the sculpture department at the university at the same time she was studying. It was so exciting to see her blossom. I like to pretend that I nudged her on her way … but her obvious skills and talent would have shone through inevitably … of that, I am sure.

This work was one of an incredible series of carved wooden sculptures she produced in her fourth year. Sublime. She was 21 years old! I wanted it badly … but a friend got in first.

Do you have a hobby? What is it?

Hobby? Not sure. My work is my pleasure, my trade and my hobby. Music is another pleasure, I suppose … a hobby of sorts. I sometimes crank up the sounds in my studio and accompany this on my bass guitar.

The one unusual item you can’t live without?

I had to beg Sanell for 20 years to get a pool built in our back garden. It took me seven years to convince her to have kids. I don’t know if she is stubborn or if I am persistent. So now we have both pool and kids. A good mix, I think.

The pool filtration system runs a UV light to nuke the algae and other shit out of the water. It pulses copper and silver into the system when needed as well … it is attached to an automatic hydrochloric acid drip feed … and is monitored online.

All I have to do is take a copper test and register it online once a week. No hunky pool cleaner for Sanell needed, I’m afraid. I have become one of those dull people who gets a kick out of pool banter. #sad. So, my copper testing kit has to be the unusual item that I can’t live without.

Who was your high school celeb crush?

Too many to mention, but Bianca Jagger. Shelley Duvall. Sophia Loren. Patti Smith. Jane Birkin. Chrissie Hynde. And all three of the original Charlie’s Angels. I might be a slut.

Three songs that you’d take to a desert island?

Have you come across the radio podcast Desert Island Discs? It’s a BBC radio production and has been going since the late 40s. They interview people of interest – musicians, writers, scientists and the like – who talk about their lives and choose eight significant tracks to take to a desert island.

To choose my favourite three songs is a cruel and unkind punishment.

My parents were hooligans and social reprobates. Brandy and Tab. Box wine. Braais and music. Complaining neighbours. And plenty of jazz. Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Oscar Peterson, The Modern Jazz Quartet, Dave Brubeck, Herbie Mann et al. These were cranked up while they burnt the meat and danced to Les McCann and Eddie Harris’s Compared to What, which is my first choice.

We take the education of our kids seriously. As a result, their DJing skills are impeccable. On our drop-offs and travels, Cat Power, Alt-J, Suzanne Vega, The Police, The Clash, The Beach Boys, Astrud Gilberto, Elvis, Bowie, The Cure, Earth, Wind & Fire, José González, The Gorillaz, The Beatles, Kool & the Gang, Sade, Feist, The Kinks, Kraftwerk, Daft Punk and Michael Jackson, among others, blast us on our way.

One morning Kai, aged four, piped up from the back seat on the way to nursery school and requested: “What about a little bit of Moby?” Their education is complete …

This morning Kai put on Elvis, The Gorillaz and Daft Punk. Lo put on Stan Getz and Astrud Gilberto’s Corcovado (Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars), which is my second choice.

My final choice is impossible. Anything by Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix or Prince. Anything produced by Lee “Scratch” Perry. Ali Farka Touré. Talking Heads. Fela Kuti. James Brown. Chet Baker. George Clinton. Leonard Cohen. The xx. Portishead. Massive Attack. I have various Amapiano sounds on rotation when I work. Bongeziwe Mabandla. 340ml. And on and on …

Two artists who I discovered fairly recently are Jacob Banks, the Nigerian-born English singer whose song Slow Up is a contender, and Beth Hart who belts out blues and rock-tinged songs … and has got some heavy-duty pipes. She has thankfully survived serious addictions. I saw her live a few years ago – her version of Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit is haunting as shit – but my final choice will have to be Hart’s song, I’d Rather Go Blind.

The satirist speaks to the FM about his exhibition titled Brood and the new sense of tenderness and vulnerability in his work

“I’m not going to stop throwing stones,” artist Brett Murray says as we walk through his latest exhibition at Circa Gallery in Joburg, as if to reassure me.

For most of his career, reaching back to the 1980s, a steady stream of satire has run through Murray’s work. At first it was aimed at the apartheid government, taunting and mocking the authoritarian state and its officials. In the post-apartheid era, as he sums it up, his work has explored “notions of identity, geopolitics, fascism, corruption and the like”.

As much as he self-mockingly interrogated his own place in the country’s emerging new social order, he also aimed his satirical slings and arrows at the new political elite’s vices: greed, corruption, hypocrisy, pretension, power lust and so on.

Perhaps most famously — or notoriously — in 2012 a piece called The Spear broke out of the rarefied context of the art gallery and into the public consciousness as few artworks manage to do.

Murray’s depiction of then president Jacob Zuma in the style of a Soviet poster of Vladimir Lenin, genitals bared, touched a nerve. The ensuing furore involved protests outside the gallery, picketing outside Murray’s home and death threats. The president wasn’t above going to court to try to have the picture taken down (even after it was reproduced online countless times around the world). Ultimately, the artwork was vandalised by members of the public.

The Spear referred to Zuma’s 2006 rape trial, drawing parallels between predatory politics and sexual exploitation. It involved an accusation that Zuma was coercing narratives of liberation for his own political posturing and self-aggrandisement. It hinted at a strain of Soviet-style authoritarianism running through the government’s character that was at odds with its democratic principles. It was also, as Murray has put it more simply, “a dick joke”. (Umkhonto we Sizwe, or MK, the ANC’s military wing, means the Spear of the Nation.)

But the artwork was also accused of treating the issues surrounding representations of black male sexuality and black bodies in general insensitively, and even perpetuating damaging stereotypes. The main force behind the popular objections (rather than the rarefied art world commentary), however, was that it was disrespectful to Zuma.

At one point in our interview, Murray grumbles: “Can you believe that people still want to talk about this?”

The debates surrounding the artwork were indeed done to death. The Spear became a bit like the hit song that makes a band famous, but which they begin to loathe for the way it comes to define them.

It turns out, however, that The Spear has ongoing currency. First, the disgraced former president is in the news again for his involvement with a new political party named MK. Russia’s violent and autocratic president Vladimir Putin grinds on with an ideological war. A sexually predatory populist leader threatens to assume the US presidency once again. No wonder people still want to talk about it.

The last thing to say about The Spear is that it is perhaps the most prominent example of Murray’s uncanny ability to capture the mood of the moment and concentrate it in a deceptively simple, immediately comprehensible image. He’s a lightning rod; a capturer of the zeitgeist. (It’s an ability that has also seen him accused of being superficial, of making artworks that amount to little more than zingy one-liners — but some one-liners last hundreds of years, and a simple image can end up being emblematic of an era. Perhaps The Spear came close.)

"That moment of panic and fear … forced me to seriously look down at family and children rather than look up and out at [other] people"

Brett Murray

New directions

If part of Murray’s artistic ability involves distilling the temper of the times in an image, what to make of his latest exhibition, Brood?

It is made up mostly of tender, emotive animal figures, some alone, others in pairs or groups, dealing with themes such as fear and anxiety. They’re not exactly humourless, but they’re more likely to elicit a sympathetic smile than a derisive snicker. They tug at the heartstrings.

This is not satire. These works are not argumentative, they’re meditative. They’re not subversive, they’re introspective. They’re not about intellect, they’re about emotion. They’re not about politics, they’re about relationships.

Brood refers both to family and to a kind of worried thoughtfulness. Murray explains that the shift began with lockdown and a project he wasn’t sure he’d even exhibit. He’d set up a studio at home, and carried on working as a kind of therapy or meditation. His subject matter was what was immediately around him — his family. He created a portrait of one mischievous son as a monkey; the other — “wise beyond his years”, says Murray — as an owl. He made a portrait of his wife as a rabbit, after her love of rabbits and the Japanese tradition of placing a rabbit sculpture outside one’s house to bring good fortune.

Something resonated and he carried on making these family portraits — he uses the word “avatars” at one point — exploring feelings that seemed pervasive at the time such as anxiety, isolation and fear, but also intimacy, tenderness and hope.

There was a fundamental shift from depicting what he calls “perpetrators” — the politicians and public figures who represent certain evils and vices, and who have traditionally been his targets — to the people close to him. “That moment of panic and fear … forced me to seriously look down at family and children rather than look up and out at [other] people,” he explains.

Those pieces did eventually come to form an exhibition called Limbo, referring to that particular in-between time. But that might have been a slight misnomer. When Limbo showed in London in 2021 and in Cape Town in 2022, he noticed that, despite the period of limbo being over, people nevertheless “responded to [the works] in an emotional way”.

“I realised that the kinds of anxieties that were specific to the pandemic [still] … resonated,” he says.

A post-pandemic global climate — he mentions “global warming, the rise of [the] right wing, xenophobia, the refugee crisis, the Ukrainian war” — also manifested, he found, in a nonspecific sense of doom without a clear target or symbol for satirical attack.

Murray also mentions a certain saturation with news and politics. “I just look at the pictures and the headlines and I can’t go any further because it feels like we’re stuck in Groundhog Day,” he says. He sees “the same stories ... as 15 years ago”.

At the same time, not unlike the lockdown experience, the apocalyptic global political climate really brought home the importance of family and the things that really matter: relationships. “Those experiences determine who you are,” he says. “I think this [exhibition] continues to reflect that and celebrate it in a sort of melancholic way.”

"[Covid] was a reminder that we are all, as human beings, literally breathing the same air … across the world."

Brett Murray

Portraits of a family

The cute and cuddly forms of his animal sculptures might once have been deceptive — expressing, as he puts it, “a weird paradox that these things that are comfortable and playful to look at actually aren’t”. They’re designed to draw you in and then “pull the rug out from under you” when you discover that they’re describing, for example, “patriarchs and war criminals”.

In Brood, he’s used a similar lexicon to express tenderness and affection. These figures are not so much symbols as characters — they’re portraits of himself and his loved ones. As much as he talks about cartoon characters familiar to him and his children — Dumbo, Curious George — influencing these works, he’s also become fascinated with netsuke, Japanese miniature sculptures, for their simplicity and expressive character.

He goes into raptures about marble, which he’s taken to working with recently, in addition to bronze. “At the risk of sounding pretentious, it’s got a different soul to it. I don’t know what it is. It’s the quality of it … the actual life of the veins,” he says. “So it was almost through a different material that I gained confidence to make things more sentimental [and] personal.”

But that’s only part of it. It is testament to Murray’s skill as a sculptor that he can pack so much expression into such pared-down forms.

So, what might Murray’s sea change tell us about the zeitgeist? What, if anything, does it mean that one of its most sensitive barometers has shifted his perspective so dramatically?

It’s not quite a symptom of political disengagement, but what he terms “melancholic withdrawal”. Of the pandemic, Murray ventures: “I think it was a reminder that we are all, as human beings, literally breathing the same air … across the world.”

In the uncertainty and our awareness of our fragility, Murray’s new work returns to familial bonds. Paradoxically, withdrawal into the private realm also reminds us of our common humanity. “We’re all the same,” Murray puts it simply. And in that, perhaps, is a shred of hope.

The soft heart of a stone thrower

Beyond words: Brett Murray’s latest show Brood, which is on at the Circa Gallery in Johannesburg, consists of 24 sculptures and reliefs, devoid of the text with which he has come to be associated.

Critics, they can make you cry. One of South Africa’s most in/famous artists, Brett Murray, has an exhibition that has just opened at the Circa Gallery in Johannesburg. It is his first that has none of the text work that he enjoys using in his art.

The self-deprecating Murray tells me, on a Zoom interview earlier this week, the story of an encounter with one of the country’s most respected artists, academics and curators, Karel Nel.

“He said he thought that my strength lies in the three-dimensional work, the marble work, and the bronzes. About the text works, he just said, ‘Those are like subtitles,’” Murray says with a chuckle.

“Yeah, so I kind of laughed — and then I went home and cried because he just made two-thirds of my practice … obsolete.”

Over his 40-year career, Murray has always engaged with words.

“Since I can remember, I worked with language — language and image — and sometimes implicitly and sometimes explicitly,” he says.

His striking new 24-piece show is called Brood. And while Murray has let the simplified forms and materials of silent animal avatars do all the talking, he still seriously plays and works with language.

“The idea of ‘brood’ was a double meaning: one’s brood, your family, and to brood over something. So, it was sort of working between those ideas,” he explains.

Created during the hard lockdown at the onset of the pandemic, Brood is a body of sculptures and reliefs; among them marble elephants embracing, a family of bunnies titled Witnesses, and groups of sad-looking bronze monkeys huddled together.

It is clear that the artist was thinking of his own spouse, their two young sons and their lives. And the lives of others.

“They are kind of avatars … which enabled me to try and articulate my relationship but, potentially, our shared relationship with our family and with our friends in times of catastrophe, in times of stress, in times of struggle.”

It is not a radical change for the artist who was mired in controversy 12 years ago over his work The Spear. It parodied Jacob Zuma, who was then president, in a Lenin-like pose with his genitals exposed and unleashed an angry backlash.

It formed part of the Hail to the Thief II exhibition at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg.

“Brood,” he says, “continues with themes established in my previous body of work.

“Although, historically, most of my work metaphorically aims satirical arrows at perceived ills in society, and while this is certainly cathartic, I have only recently worked out that the process of making is independently therapeutic.

“Where before my animal sculptures might symbolically mock predators, policemen, politicians, oligarchs, sycophants, the corrupted and the like … during lockdown I felt impelled to look closer to home for my subject matter.”

I ask whether he has gone soft or more subtle with the almost melancholic Brood.

“No, it’s not a question of subtle, I don’t think,” Murray replies. “People have responded … there’s almost an emotional response to the work, which is great, because it seems to have resonated in this age, even though I’m so cynical about my own stuff…

“And, you know, no longer the sort of … Che Guevara of the southern suburbs [of Cape Town],” he says with a giggle.

“I’ve hung up my beret. So, yeah, there is a softness, but I’m 62. I’ve come to an age that I don’t care what people think anymore. You know, I’m making stuff.”

Before our interview Murray sent me a lovely reflective note.

“What I thought I had produced was a single-issue body of work,” he wrote. “A response to the pandemic reflecting our mutual fears. A fragile tenderness. Our collective breath had been held for a few years.

“However, on seeing the works installed post-Covid it seemed a broader reading was possible. Implicit rather than explicit.

“We are currently gripped by uncertainties; global warming, nationalism, xenophobia, a failed state, the refugee crisis, the rise of populist right-wing agendas, wars, genocide … and more.

“These weigh heavily on our ‘families’. The new works extend the themes of familial intimacies and brooding contemplation. They describe a world of trepidation and vulnerability. Melancholic by default. Hopeless yet hopeful.”

I prod him about the contradictions we are experiencing. On the one hand, there’s the gentle intimacy of his brood, his family, that is so beautifully reflected in the work at Circa. On the other hand, there is the daily horrors of children being killed in the genocide in Gaza.

“We live in a world of contradictions. I mean, living in South Africa, the contradictions of living in a house with a car and a full fridge where most of the country don’t have that and will never.

“That is the country of contradictions that I was born into.

“Similarly, the contradictions of the horrors of war, in all the wars that are happening all over the world, and in Ukraine, Yemen and Palestine.

“It’s therapeutic for me to come to a quiet space, come to my studio, whether I’m making these objects or other objects. Because it’s horrific when you see the images of kids and families,” he says.

It is just a brisk 10-minute walk from Circa down Jan Smuts Avenue to the Goodman Gallery, where Murray’s The Spear was hung in 2012 but it will transport you back to a tumultuous time of controversy with the artist right in the raging centre.

The painting was vandalised, it prompted protests. The ANC went to court to have it banned and wanted the image removed from public view, including on newspaper websites.

It was ironic, because Murray was actively involved during the anti-apartheid struggle, using his art as a tool for left-wing organisations in Cape Town. He experienced censorship in his earlier life as an anti-apartheid art activist in the 1980s.

He designed posters, logos and T-shirts for the Community Arts Project. They printed their T-shirts at Community House in Cape Town, which housed various trade unions, the United Democratic Front and other left-aligned organisations.

“We used to print T-shirts and stuff for funerals — like ANC guerrilla Ashley Kriel’s funeral — and marches,” Murray told me in a previous interview.

“One of our members designed the Food and Allied Workers Union logo which is still in use now.”

Murray and his comrades had a particularly narrow escape one night. They had just left Community House after a workshop when a limpet mine rocked the building.

“I’d say that’s an attempt to censure and censor but you kind of forget that history,” Murray said with a wry chuckle.

“Much of the language of the 2012 exhibition at the Goodman was kind of Soviet propaganda, the sort of posters that I designed for the struggle during the 1980s,” he said.

He used the language of Soviet iconography, for this exhibition, “with a rejig in the South African context”.

One of them was an iconic image of Lenin done in the Fifties, “so I put Zuma’s head on it. And I thought that was in fact enough as a painting — sort of taking the piss out of the new elite.”

At the time, he was focused on social commentary and “you have a devil and an angel sitting on each shoulder, and you get some time to listen to it, and sometimes you go, ‘Fuck it!’ and you listen to the devil”.

As he admits, “I like to be transgressive, you know, I read Foucault and Derrida, but I also like slapstick and I like funny one-liners. So, I painted a dick on [the Zuma painting].

“And then I thought this may be a bit much,but I just kept carrying on working … and then, more out of laziness than anything else, I’ve decided to keep it — it was a one-liner dick joke.”

Murray’s name and address were in the phone book and people started to gather outside his studio, at his house. The spokesperson for the Shembe Church said at a rally he should be stoned to death.

“I had to leave my studio to take my family to a safe house. So, it was a pretty uncomfortable time,” Murray told me.

“I wasn’t used to it; I wasn’t used to the spotlight. That was very uncomfortable. And scary.”

It is not surprising that the artist is relieved that is all in the past. As Brood shows, his artistic work has also moved into a different direction, and, as he tells me this week, “My interests had been shifting from perpetrators to people and I had been wanting to transition from an accusatory position to one that is more compassionate and empathetic.

“Something intimate and kinder,” and his mischievous chuckle again. “Not exclusively though … I remain a stone thrower at heart.”

Art of the week: Brett Murray’s Fiscal Cliff and Wealth Management

Wealth Management by Brett Murray. Image supplied.

Brett Murray made a name for himself with his controversial – and rather revealing – painting of Jacob Zuma. Now he’s turned his sharply satirical eye to the world of finance.

Cast your mind back to 2012, when Jacob Zuma supporters protested outside Johannesburg’s Goodman Gallery in anger over artist Brett Murray’s, should we say rather revealing, painting of their boss, titled The Spear.

Remember how the artwork was later defaced by two of these acolytes and that the ANC, when it still liked Zuma of course, briefly took the artist and gallery to court in defence of its great leader, who was president at the time?

What a difference 12 years makes. It’s hard to imagine the current iteration of the ruling party doing anything but smirk over that piece of cultural criticism. How leadership changes, politicians pivot and artistic taste wavers with such ease.

Murray might be a decade older and now represented by Everard Read, but he is lightyears more consistent than the flip-floppers running SA Inc. This is certainly true of his career-long knack for societal commentary through art.

Murray is wont to say that he’s softened in his “old age”. He spent the Covid lockdown and the time since crafting a world of animal-like sculptural avatars that underscore the importance of family, love and looking after each other, so perhaps there’s some truth to his claim of being softer. Bunny broods aside, there’s still a satirical self-reflective court-jester energy to the work the Cape Town-based artist now produces.

Comments on capitalism

Take his latest works, titled Fiscal Cliff and Wealth Management. In both, Murray has turned his critical gaze on the world of capitalism and finance. Where the first work, a sculpture, is concerned, it doesn’t get more metaphorically obvious than copulating hyenas. They’re smiling maniacally as one nudges the other over a cliff.

What average South African wouldn’t identify with that image? Taxes, the cost of living, our desire for fine things, unemployment – it’s a constant entanglement at the edge of the economic precipice.

Characteristically, Murray doesn’t take his own work too seriously, though the message is piercing. “Are they playing or fucking? Well, that depends if you want to get the work for your kids’ room or if you want it for your office,” he says with a laugh.

“The image is basic and crude but it’s a commentary on us fornicating at the trough of indulgence and greed and avarice,” he says – though he’s quick to include himself in the capitalist miasma. “I suppose I’m in the privileged classes. That doesn’t stop me from pointing fingers with full understanding that four fingers are pointing back at me,” he says.

Murray says he understands that he is part of the problem, at least in the context of the chasm between the rich and the poor in South Africa. “But at least having some level of self-reflection keeps you honest. I think if it was just flag waving and throwing stones without that and understanding, then these works might just be insults,” he says.

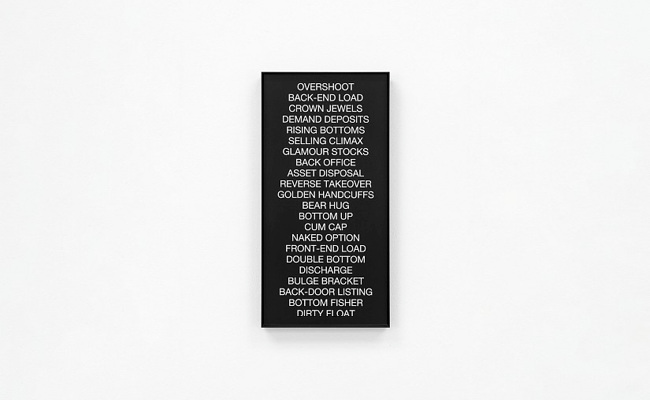

Wealth Management is more literal in its treatment of the financial realm and with its playful use of only words. It is vintage Murray: “selling climax”, “rising bottoms” and “naked options” are all in the mix.

“I bought a book of terms used in the investment and banking industries published by Business Day almost 20 years ago,” he says. “I’m not sure why. I know nothing about either industry but thought that if I put the publication under my pillow, perhaps I’d take on some of the financial nous by osmosis. It didn’t work.”

The book floated around Murray’s studio and after paging through it, he came across a few terms with hilarious double meanings. A glance at this salaciously suggestive list is revealing of banking’s instinct for subtle insurgency. (Ed’s note: could you explain, simply, what all these financial terms mean? No googling).

Unlike the ANC in 2012, we doubt the stockbrokers, bankers and Reserve Bank economists are going to be picketing outside Everard Read anytime soon – for one thing, you’d want to believe they’ve got better art sensibility and take themselves less seriously than our politicians.

Either way, instead of laughing all the way to the bank with their piles of moolah, perhaps they should pick up a highly collectable Murray. Next year there’s a retrospective of his sculpture at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town, and that’s bound to do great things for their value.

* Fiscal Cliff Bronze, 2024, Edition of 6, R285,000 each; Wealth Management, 2024, Edition of 8, R40,000 each. Everard Read

Brood: Personal Notes

Brett Murray working in his studio in Cape Town, South Africa. Photograph by Mike Hall.

This group of sculptures continues with themes established in my previous body of work.I hadn’t finished yet. I suppose you never do.

During hard lock-down and at the onset of the pandemic I set up a studio at home. Although historically most of my work metaphorically aims satirical arrows at perceived ills in society, and while this is certainly cathartic, I have only recently worked out that the process of making is independently therapeutic. I am a slow learner. I just need to keep busy to stay sane. I titled the show LIMBO. The state of us then.

Where before my animal sculptures might symbolically mock predators, policemen, politicians, oligarchs, sycophants, the corrupted and the like… during lock-down I felt impelled to look closer to home for my subject matter. My interests had been shifting from perpetrators to people and I had been wanting to transition from an accusatory position to one that is more compassionate and empathetic. Something intimate and kinder. Not exclusively though…I remain a stone thrower at heart.

I have been researching the small Japanese Netsuke kimono fasteners for a while. Deliciously refined and paired down decorative mini sculptures carved in stone, wood, or ivory. Sometimes cast into metals and mostly of animals. In my inquiries I came across the Japanese tradition of placing a to- scale wooden sculpture of a rabbit looking heavenwards outside houses and businesses as charms that might bring prosperity, good luck, and fertility.

This seemed like a good place to kick off my lock-down therapy, so I started by making small symbolic portraits of the four of us at home as animals. My partner, our two young boys and myself. We have an odd collection of small animal sculptures and toys around the house. These inspired. As do the Ghanaian Asante king’s linguist’s staffs: exquisitely carved wooden figurative finials, finished in gold leaf, that describe through visual proverbs each king’s strengths and visions.

Sanell loves rabbits and we certainly needed the good fortune, so she was portrayed as a rabbit. Lo is wise beyond his years and was represented as an owl. Kai as a mischievous monkey. All three are looking to the heavens for guidance or as witnesses to an impending calamity. I hold my hands and look down anxiously as a monkey and a father. In hope and in fear.

These first four seemed to resonate effectively…so I extended the series, describing the intimacy and anxiety of isolation and of social separation that has been a universally shared experience and somehow paradoxically binds humanity together. Hopefully.

What I thought I had produced was a single- issue body of work. A response to the pandemic reflecting our mutual fears. A fragile tenderness. Our collective breath had been held for a few

years.

However, on seeing the works installed post covid it seemed a broader reading was possible. Implicit rather than explicit. We are currently gripped by uncertainties; global warming, nationalism, xenophobia, a failed state, the refugee crisis, the rise of populist right-wing agendas, wars, genocide…and more. These weigh heavily on our ‘families’.

The new works extend the themes of familial intimacies and brooding contemplation. They describe a world of trepidation and vulnerability. Melancholic by default.

Hopeless and hopeful.

Memories in ‘Limbo’: Brett Murray’s bronzes sculpt ghosts from my childhood

‘Limbo' by Brett Murray at Everard Read, London. (Image: John Adrian)

The creatures gazing outward to some imminent event, exemplify a state of innocence, not still, but thrust headlong into the experience and therefore capture something, a mere flash, of the rush of a soul from itself.

pale were the sweet lips I saw,

Pale were the lips I kiss’d, and fair the form

I floated with, about that melancholy storm.

— John Keats, On a Dream

Over a video call Brett Murray speaks to me in a Cape Town accent I haven’t heard for a long time. He sits at his computer, surrounded by children’s things – many recognisable from my own childhood memories: action figures, two large and slightly deflated golden birthday balloons say “11”, Halloween decorations, puzzles, Lego constructions, brightly coloured children’s books. He tells me that when he’s in a bad mood, Sanell – that is, his wife, Sanell Agenbach – says to him, “for fuck’s sake Brett, go and make something”, and he disappears into his studio for a couple of hours. He explains that his working progress, like this, is quite basically cathartic. He’s in a discoloured T-shirt, which gives him the appearance of having just come out of one of these therapeutic sessions.

I ask him if it was at all difficult to use these same “tools” used on politicians as he has on his family. Namely, the same reduction of form, the same methods and techniques, which in previous exhibitions have been used to ridicule, mock and parody.

“In this latest exhibition of bronzes these techniques are used rather to represent loved ones,” I say to him. “What was used to attack in this work is now used to express love; so it feels like mockery becomes something endearing, like the silliness of an inside joke, a kind of teasing.”

Murray’s new bronze works – which were exhibited for the first time in the UK at the Everard Read Gallery in London in November 2021 – seem to move inward, towards silence rather than towards speech. Even the titles of the works are single monosyllabic words (such as Loom, Witness, Shield, Omen), showing an awareness of the weight of language rather than the readiness to speak out that characterises his earlier work.

The same hands used in the past to caricature the powerful are used, in a manner of speaking, to tickle the child-feet of his sons, to be playful and tender and peel the fruit of love to its pulpy interior. But he seems uninterested; what seems to me to be a contradiction or a difficulty is, for him, completely easy and natural, an organic process:

“For a while now, I’ve been looking for a different material. I was finding the stark, very black patinas of my bronzes had a particular language… It was almost always about perpetrators rather than about people. The same animals that I am using now were the targets of my vitriol. They were the patriarchs, they were the predators, etc. And I had been wanting for a while to do something that was about people, that was more human based,” he says. “You know, that was about my family perhaps, and about my friends, and about us; so what you were saying – to rather look internal, and look inside.”

His eyes close in concentration as he speaks, emphasising with easy gestures that remind me of my father’s hand movements.

“It came to me when I started working with marble on my last show. I had made a series of maquettes. They are light grey in colour, a much lighter material that I make in preparation for my bronzes.

“I had half a dozen of these in my studio and the tone and the colouring, and what they started resonating was a vulnerability even though they were about perpetrators. And it was that I was looking for. And on the same day, Sanell walked into my studio and she looked around and she said, ‘these would look great in marble’. I didn’t know what marble would do to these forms. And actually they have made them much more intimate, much more sensual, much more quiet,” he notes.

“There’s silence,” I say.

“In the marble specifically,” he agrees. “Whereas before, in the bronze, you might reference military things and shields and armoury. In the marble, there is a totally different resonance. And it’s the physical nature of the marble that encouraged me to loosen up, actually, for these same forms to be more intimate and private and able to talk about vulnerability. Even though there is only one marble in this show, which is from the previous show. It was what the marble brought to my forms which I decided to pursue.”

My earliest experiences of art, like most, came from my parents. Both artists themselves, our home was full of images on the walls, objects cluttered the surfaces. A large framed replica print hung in my parents’ room: a black-and-white photograph of a woman leaning her head into the embrace of her own folded arms. It was beautiful, but I was too young for such serious ideas. To me, the photo was simply there in the same way the mahogany wardrobe was there; or the way the wooden carved angel missing an arm was there; the way mom’s dresser on which the angel stood was simply there. The picture was so still. It preceded my own existence, in a sense, was already in the world, or more precisely it made up the world around me, my notion of home, gave me a context, held me in this environment, as my mother would hold my head to her in an embrace so familiar that it could dispel all troubles and all thoughts and allow my own presence to be felt within myself slowed to the tempo of her stroking hand.

I left the house to go to school, to play in the street or the garden, while the picture stayed stationary, reliable and ever-present in the recesses of my mind, as a synecdoche of that home. There it hung, day after day, undemanding of my attention. I did not wonder who the woman was or why she was photographed in such a peculiar way, a white aura around her.

On occasion, I simply stared at it, sometimes at the fine dust particles that had accumulated in the corners adhering to the glass. And like this, the vague animals of my thought stirred, moved slowly at first, not around the picture, but from it, held by its familiarity, they wandered aimlessly through my consciousness, through the recollections of my day, perhaps, my week, school, friends, family, and even deeper into memories no longer attached to clear images but just the impressions, fragments and sensations left behind.

This all seemed to arrive as if directly from the surface of the photograph itself like spindrift or as light emanates from the filament of a light bulb.

It was only many years later that I even heard the name Man Ray, and another 10 or so years before I came to associate his photography with someone I had fallen in love with, and so came to appreciate his work with some intelligence.

A photographer herself, she lived in an old, rundown sweet factory in Limehouse near the Thames which had been turned into ramshackle artist studios, graffiti covering every wall. And it was from there that I took the Underground, in a marble-coloured fog, to Chelsea to see Brett Murray’s exhibition. That was the last time I visited her there, and so it was to her that my mind bent as I entered the gallery.

Murray is a close friend of my parents and his own work was among the many objects around our house. His pop-art wall lights especially, which, my father told me, he made for years to pay the bills: a penguin in a tuxedo serving a martini hung in my bedroom; a pink panther with an Afro, was in the lounge; and two hearts with the Afrikaans word liefie, “my love”, hung also in my parents’ room.

You could imagine Murray’s exhibitions to be family affairs, and in many ways they have remained so, the exhibition in Chelsea being the first I’ve seen without my family present. In this way, despite the explicit political content of his work, Murray’s presence in my own imagination has always belonged, like the Man Ray image of the woman resting in her grey-pale arms, to my ideas of home and the warm interiority of childhood.

In fact, I felt for a long time stupefied by the political content, which always escaped me as a child, but which also remained like a shroud, or rather like a vapour of mystery and importance around the sculptures, prints, paintings, posters. At these exhibitions invariably there would be a discussion about the current political situation and, not understanding, I listened attentively for a name I might recognise – the playful double syllables of Tutu or Winnie – and mouth these quietly to myself as though this was the key to adulthood. “Politics” came to represent to me everything that was secret, important and difficult about art and art, in turn, came to symbolise growing up.

Murray’s show at the Everard Read Gallery in London consisted of about a dozen small plinths, each with a small bronze sculpture, arranged in a kind of grid to cover the room so that one must walk between them to see each of the works. A deep-red-painted wall as a backdrop, a Scorsese red rather than a communist red, which in itself seems to mark a movement from Brett the agitation-propagandist to Brett the aesthetician.

The sculptures appear to be of animals – rabbits, donkeys, birds, gorillas, monkeys – rendered in a playful, stylistic manner, like children’s soft toys or cartoons. Some are alone, some are in a tender embrace, others seem alienated from one another, contemplative. They were illuminated reverently by spotlights, in which they seemed confused and lost, even blind, I thought. They reminded me in this way of a man I had seen one evening peering strenuously out of his brightly lit apartment, cupping his hands to his eyes, trying to make out the street below. All the passers-by, including myself, could see him illuminated perfectly in his lightbox, but he, surrounded by light, was completely blind to everything outside his little world.

Each sculpture seemed also alone on its own lightbox, what Murray described to me as “awkward, isolated islands”, blind to the other’s existence, blind to me and the other gallery visitors. Most of these animals look upward as though at the sky, in anticipation for something to arrive, happen, for an answer, for meaning.

Heartbreak, according to Roland Barthes, renders the world thunderstruck: “various objects – whose familiarity usually comforts me – the gray roofs, the noises of the city, everything seems inert to me, cut off, thunderstruck like a waste planet.”

These animals around me are like Adam and Eve, suddenly aware of their nakedness and shame, awaiting the fall: a sculpture of two donkeys called Tether, isolated from the world in their embrace, look up as if they have just heard the first crack of thunder.

Writing now, from a few notes and memories, Murray’s small sculptured creatures reveal to me something of my state of mind at that time.

Lost and frantic, identifying with the émigré protagonists of the novels I was reading, it seems to me now that I was living in a kind of mist. I can only describe this as a fugue state in which my previous life, my previous self, lived only in my memory. Fugue from fugere means “to flee”: a fugitive from love, from childhood, and from home. The sculptures, so intimate and anxious, made from the same eye, the same hand, as those objects of Murray that hang in my parents’ home so very many kilometres away, where I used to sleep to the sound of the ocean in the distance, felt like ghosts of the past. The colours of these sculptures, their earthy, soft patinas, represented the landscape of that home, the colours of the dry soil that the protea emerges from, the rocks and caves damp from mountain springs, the fynbos scorched by seasonal fires.

Beset by memories and history, I felt their sad comfort turn to something that reminded me of the mushrooms in Derek Mahon’s famous poem, who beg us to remember them, the lost people of Pompei and Treblinka. Under scrutiny, these memories, my own and the entire terrible history of South Africa even, seemed increasingly fictitious, like I had created them myself. Rather than comforting me the deteriorating memories now represented by these small, wide-eyed creatures threatened to derail my entire sense of self.

“An image that came to mind, when I saw all those figures looking fairly scared and terrified, I mean this sounds fucking pretentious, but it reminded me of – in Pompei and in earthquakes and sandstorms, you have skeletons that have been exposed in poses of intimacy. There is a beautiful mother and child, literally like my sculptures, looking up at impending doom. Then they’re exposed, and I suppose as a human being you relate to that there is a kind of relationship you have with that. The kind of intimacy and pathos. It was a surprise,” he explains.

I think of Barthes, who in Camera Lucida gives an account of mourning through photographs. He becomes frustrated by the many photographs left behind of his mother’s image because, to him, none of these images captures her essence. Eventually, he finds one that does this for him, but curiously, it is one of his mother as a child, before Barthes has been born. He writes however that in this photo a certain pose or gesture brought forward the realisation that the light which came off her summer dress literally is the light which impressed itself, imposed itself, or exposed itself to the strip of photographic film, the same light literally which Barthes receives with his eyes. He says that contrary to the photograph as merely a fiction as Susan Sontag would say, what is recorded by the camera, however rehearsed, set-up, fictionalised, has without a doubt for a moment paused, posed, still, even for a split second, in front of the lense.

Murray’s sculptures are not photographs, but he frequently refers to them as “exposed”, like the ash figures of Pompei. Through the zoomorphism, through the stylistics, what Barthes calls the studium (“more or less stylised, more or less successful”), a certain posture, a certain essential characteristic particular to his child, his wife, to himself, is held in the sculptures.

This is what is captured, exposed as though swerving toward me. The secret intimacy of a family that is not mine, but also the secret intimacy of being (Barthes’s frustration that even this photograph is in fact, under his scrutiny, blurred, uncertain and foreign to him). It is at the same time from where I am pricked, made to feel moved toward and away like the vertices of the hyperbola (“to throw beyond”) swerving in and away from each other.

The punctum, Barthes’s word for that which pricks me in the photo: punkt, the German word for “a point, a full stop”, but also a small hole, puncture, an ordering and a rupture, an asymptote. “The punctum is a kind of subtle beyond,” Barthes says, “ – as if the image launched desire beyond what it permits us to see […] toward the absolute excellence of a being, body and soul together.”

If the little face of this bronze monkey, gazing up at the viewer, were even a fraction lower, or its posture a little straighter, a little happier, it would not have captured the playfulness of Murray’s son so accurately. A little sooner or a little later, this perfect pose would have been missed; it is exposed at the right degree, the right angle, the right moment in time.

The bright little rabbits looking skyward, Witness and Protect, are inspired by the formal precision of Netsuke button fasteners. The capture of the sculptures, the eidos, is so slight, so deft, so quiet, so seemingly natural, that its contradictions – what seem to be the impossibilities of the execution – are overcome with the naturalness and ease of a breath, the naturalness with which Sanell could say “these would look great in marble”.

I return to the image of the two monkeys in their moulded embrace named Shield. As I had once stared at the Man Ray reproduction in my parents’ room, and like the anguished eyes of the philosopher who pores over the image of his mother as a child, my stare was full of hands, full of mouths. It leached to the light they fed me which rose to meet me faster than my eyes could drink. And here, myself floating just above this sculpture, I experienced a strange stasis, my breathing slowed to the pulse of their slow, undulating postures, arriving. And somewhere inside me, beneath the troubled surface of my consciousness, I felt calm.

My desire to flee from my own loss of identity to one which seemed to me held, fixed, pure, within the frozen bronze postures of these animals, was an attempt at surrogation, a nostalgia for meaning, a lonely rage. But in fact, the creatures gazing outward to some imminent event, exemplify a state of innocence, not still, but thrust headlong into the experience and therefore capture something, a mere flash, of the rush of a soul from itself. In this way, like a pencil hovering above the image it draws, like a strange moon above a planet, I experienced these bound figures as a kind of map of my own way.

My earliest experiences of art, like most, came from my parents. Our home was filled with artworks and pictures on the walls. Collectable objects cluttered the surfaces of the shelves, the piano, the tabletops and bookcases. Among these many objects, tastefully arranged, were Brett Murray’s cartoon wall lights. I was told by my Dad that he made these for years to pay the bills as a young struggling artist. For those who haven’t seen them, they are made of colour tinted perspex and metal frames, simple and rough like graffiti stencils. And they have the mischievousness of graffiti too: tongue-in-cheek, self-reflexive, indulging in ‘bad taste’. A penguin in a tuxedo serving a martini hung in my bedroom; a pink panther with an afro in the lounge; and in my parents’ room, above their bed, two hearts with the word liefie, ‘lovey’, written in calligraphy on a ribbon in the style of a second-rate tattoo parlour.

Our home was not the only one adorned with Murray’s lights. They have become something of a signifier of taste for a whole generation of the South African intelligentsia. For example, when I first arrived in London I stayed for a period with a friend of my parents, a musicologist who had relocated years ago. On seeing two of Murray’s lights in the kitchen, I was compelled to say with feigned surprise, ‘–Ah, are those Brett Murray’s lights?’, which was met with such enthusiasm from my host that you would have thought I had just declared that I shared her love for Schostsakovich and Mahler.

Despite the explicit political content of his work, in my mind Murray’s sculptures, wall texts and posters, have therefore kept these associations of home, of my parents and their friends, their ironic love of kitsch, their intellectualism. As you can imagine, Murray’s exhibitions were like family gatherings for the art world of Cape Town. At these openings there would be an inevitable discussion about the political situation in South Africa. Being a child, I couldn’t follow the conversation, but I would wait with large eyes like a little owl for a name I might recognise – the playful syllables of ‘Tutu’ or ‘Winnie’ – and mouth these to myself quietly and hungrily as though they were the very marrow of meaning.

So it was on the one hand that Murray’s political satire totally escaped me as a child, while on the other its obscurity and complexity intrigued me. It covered the artworks in a kind of radiance, a promise of growing up, an anticipation for knowledge. ‘Politics’ came to represent to me everything that was serious, important and difficult about art, and art in turn came to symbolise life proper, without fairy-wheels and child-locked car windows. My pleasure, wandering around the galleries as a child while my parents and their friends conversed heatedly, was derived simply from this radiant obscurity, as flummoxing to me as hieroglyphs.

I felt that life – life proper – had not-yet begun for me, that I was in a sort of waiting room; the meanings of things were not actual but mediated through a veil of the future which would eventually be lifted. But this veil, like streetlights in a heavy mist, gave everything a wonderful glow; my naive idea of the future gave my reality to me spangled. It was a glow that concentrated around art especially, but which lay over everything, authenticating the world around me, heightening it, like when you have been swimming for hours in a chlorinated pool and emerge into a summer evening that smells of jasmine, and the gentle fairy lights, the candles and lanterns in the garden look huge, beautiful and blurred and you feel warmly detached from the lovely visions of your life passing in front of you.

To be confident or sure of one’s knowledge, to say ‘I am right; you are wrong’, is to put an end to the fantastic glow, to put an end to the firework display of imaginative and speculative thought. To call it ‘the light of knowledge’ is not the most accurate metaphor then, because it is the acquisition of this knowledge that rapidly diminishes this glow of the possible until it disappears almost entirely. I think that artists – artists like Brett Murray – are those individuals who never recovered from the diminuendo of that melody which played throughout childhood.

As an adult I can now understand the political meanings of Murray’s work. I can sense the artist’s anger and relate it to the broken promise of a new democratic South Africa, for example; I can draw connections now between Murray’s formal interests, and the formalism of Jean Arp and Constance Brancusi. I can see the work now in its historical context. I can detect Murray’s apparent disillusionment in art-for-art’s sake for a direct and political art. (What role does beauty have in the face of the brutal realities of apartheid?) I could relate this to the neo-conceptualism of Jenny Holzer and the YBA’s who were working contemporaneously to Murray. I can understand the content now and interpret it, but also I can feel something deeper that is not as clear or straight-forward. What I know now, as an adult looking at Brett Murray’s work, is what in many ways obstructs me from seeing it for its complexity. What I am interested in now is complicating my familiarity and folding the single plane in on itself.

In Brett Murray’s 1996 show, White Boy Sings The Blues, among the exhibited pieces was a striking photograph of a young Brett taken from a family album and titled, ‘The Artist as a Zulu, aged 6’. The boy in the photo is dressed up as an African, a Zulu warrior perhaps. The whole of his already then stocky physique is painted black – from his face to his feet – making the whites of his eyes shine. The boy looks serious, totally committed to his role. There is a look that seems embarrassed or even guilty and yet something tells me this may be my own projection, my need to reconcile the image. It’s a very difficult picture—difficult to come to terms with because we can see the innocence of the child but looking from our 21st century stand point, we also cannot unsee the manifestation of racist ideology. As viewers we experience a schism between these two signifiers: child and black-face, innocence and racism.

The result is an endeavour to peel the child from his political context as one would peel a fruit from its skin or the content from its form; we try to stage a rescue, recover the boy from the historical and political codes of the photo: the whole ghastly history he seems thrust into and will have to grow up folded inside of. Brett Murray exhibited this photograph again a year later in his exhibition Guilt and Innocence, shown inside of the Robben Island Prison, in which it was featured beside other family photos: one shows the artist’s family standing patriotically beside the old South African flag; another is of a young child wrapped in it like a blanket, literally this is a child folded into this emblem of ideology. Brett Murray wrote of this exhibition:

I was born in December 1961, a few months before the Rivonia trialists (Nelson Mandela and his compatriots) were imprisoned. Being born in Pretoria, into a half-Afrikaans, half-English family, where my father’s heritage extended back to include both Paul Kruger and Louis Botha (Boer presidents), disguised by my grandmother re-marrying a Scottish Murray and my mother’s history reaching back to the French Huguenots, I am a white, middle-class cultural hybrid. This was and is my comfortable and uncomfortable inheritance. The political and social forces beyond the confines of my family formed a system which protected and infringed on me, empowered and disempowered me, promoted and denied me. When I looked beyond my private experiences of loves and relationships, family and friends and of boy becoming man, the contradictions in this system, which divided my life from others, resulted in a cross-questioning of responsibility and complicity. […]

The contradiction to be reckoned with in ‘The Artist as a Zulu, aged 6’, the difficulty and complexity, is in the imaginary act of the boy’s play. Because, it is the act of play that is at once the foundations of the artist’s creative life and the very product of a racialized subjectivity. A theme, even perhaps, the theme, of Brett Murray’s work is this: his vitriol, his whole arsenal of cartoons, satire, wit seem to me in the purpose of an aggression drive directed at a Master Signfier, which changes names: Apartheid, Zuma, Authority, Self. The fight for a recovery, reconciliation, rehabilitation of the image of the child innocently playing a Zulu warrior, is an attempt at unknotting the complicated/implicated [plicare ‘to fold’] child in a systematic legacy of racism, but with full knowledge of its failure. The work is not here to make new claims of grandeur but to simply, pathetically, to fail and fail again to show something of this frustration of being bound by subjectivity.

Murray’s practice is fiercely anti-ideological, and yet, following Althusser’s thought that there is ‘no outside of ideology,’ it cannot be escaped. What becomes the target of Brett Murray’s vitriol is not only the hypocrites, the political elite, the moronic inferno, but the artist himself folded within this system. The work in a sense tries to wash the black paint from the child’s face, to remove the adult, and revive the pure imaginary state of the child, but is fully aware of the impossibility of this task. This Sisyphusian labour must be performed repeatedly in every exhibition, every sculpture. What has given the gift of imagination and creative life is implicated/complicated in ideology. I’m reminded of what Spivak says, that “we are folded with the other side.”

Perhaps this is why The Child features throughout Murray’s work in various manifestations. We could imagine it as a kind of hidden image or watermark to be recovered by the viewer. Whether the image of the child appears as a self-identification with cartoon characters like Bart Simpson, who becomes a kind of alter ego appearing and reappearing in the early work; a bubble-head in short pants; the child-like physique of the fat sculptures (mirroring and mocking the short stocky physique of the artist himself) ; the black-faced Richie Rich in ‘Rich Boy’ who holds a bag of money in one hand; the self portraits of the artist in diapers and a baby’s bonnet; and the bronze and marble sculptures which are like huge children’s plush toys showing the influence Jeff Koons’ balloon dog or flower-bed puppy. In Koons too we have an artist whose love for cartoons, toys, and sweets show an imaginary life linked to a notion of The Child. In this sense, I think, Murray’s work is only ‘completed’ when it is experienced by a viewer who retrieves the watermark, the image of the child, which carries with it something of an essence. Only once the artwork is apprehended, experienced, once this essence is impressed on us, does the work lead towards a completion.

Over a video call, Brett Murray speaks to me in a Cape Town accent I haven’t heard for a long time. I have been in London now for almost a year. The last time I saw Murray it was Easter and he was following his children into a swimming pool looking exhausted after extensive egg hunting. Now he sits at his computer in a room, behind him are many high shelves packed with children’s things: legless action figures; two slightly deflated birthday balloons, which say ‘11’; old Halloween decorations stuffed into a corner; Lego constructions and fluffy toys fallen out of favour. He tells me when he’s in a bad mood, Sanell—that is, his wife, the artist Sanell Aggenbach—says to him, ‘for fuck’s sake Brett, go and make something’, and he disappears into his studio for a couple hours. He tells me his working process, like this, is quite basically cathartic. He’s in a discoloured t-shirt covered in paint marks, which gives him the appearance of having just come out of one of these therapeutic sessions.

We are having a conversation about his latest exhibition, Limbo, a series of small, highly stylised, bronze animal sculptures that were shown at the Everard Read Gallery in London, and which I have been fortunate to see recently. I ask about the stylistic shift these new sculptures might signify, being smaller, formally softer and more introverted than previous work. He tells me it was a natural process, that he doesn’t regard these sculptures as a whole new phase, but rather as an inevitable step in the evolution of the work.

I ask him about his childhood. He tells me how he liked cartoons and comic books. And while he talks I become strikingly aware of the fact that this Brett Murray, who is reduced in size to fit digitally on my laptop screen, is a kind of cartoon version of himself as we speak, which has the bizarre effect on me of an urge to caricature him. I make a silly little doodle in my notebook while he continues to speak. I don’t do a great job of capturing his personality: not much more than a stocky little stick-man with a big smile. After all, to reduce someone to a stick-man one is forced to kill off many physical characteristics.

“Did you find it at all difficult,” I ask him, looking up from my ridiculous doodle as though it were a serious and pertinent note, “to cartoon your family? – I mean to use the same reductive ‘tools’, or the same stylisation as you’ve used on politicians as on those you love?”

In previous exhibitions of Murray’s this reductive quality is very distinctly used to ridicule, mock and parody; in the Limbo sculptures the antagonism, the demonic quality of the cartoon is quietened or refined to a deftness of capturing a likeness rather than exploiting physicality for polemics. So this violence is tempered to a playful chiding of his family; the same hands, the same techniques, used in the past to crudely caricature the powerful, are used here, in a manner of speaking, but to tickle the child-feet of his children, to be playful and tender and peel the fruit of love to its pulpy interior.

‘For a while now,’ he says to me, ‘I’ve been looking for a different material. I was finding the stark, very black patinas of my bronzes had a particular language.’ He pauses for a moment to arrange his thoughts. ‘It was almost always about perpetrators rather than about people. The same animals that I am using now were the targets of my vitriol. They were the patriarchs, they were the predators et cetera. And I had been wanting for a while to do something that was about people, that was more human based,’ he says. ‘You know, that was about my family perhaps, and about my friends, and about us; so what you were saying – to rather look internal, and look inside.’

His eyes close in concentration as he speaks, emphasising with easy gestures that remind me of my father’s own hand movements.

‘It came to me when I started working with marble on my last show,’ he continues. ‘I had made a series of maquettes. They are light grey in colour, a much lighter material that I make in preparation for my bronzes. I had half a dozen of these in my studio and the tone and the colouring, and what they started resonating, was a vulnerability even though they were about perpetrators. And it was that I was looking for. And on the same day, Sanell walked into my studio and she looked around and she said, “these would look great in marble.” I didn’t know what marble would do to these forms. And actually they have made them much more intimate, much more sensual, much more quiet.’

‘There’s silence,’ I say.

‘In the marble specifically,’ he agrees. ‘Whereas before, in the earlier bronze works, you might reference military things and shields and armoury. In the marble there is a totally different resonance. And it was the physical nature of the marble that encouraged me to loosen up actually, for these same forms to be more intimate and private and able to talk about vulnerability. It was what the marble brought to my forms which I decided to pursue in bronze.’

Limbo consisted of about a dozen plinths displaying small bronze animals. These were arranged in a kind of grid pattern to cover the room, so that I had to walk among them to see each one individually. There was a red painted wall as a backdrop, a Scorsese red rather than a communist red, which in itself seemed to mark a movement from Brett the agitation-propagandist to Brett the aesthetician. The sculptures – rabbits, donkeys, birds, gorillas, monkeys – were rendered in a playful stylistic manner, like children’s toys or cartoons. The poses of the sculptures characterised them, giving them almost recognisable personalities, so that these two could be Brett and Sanell, this one, Kai, that one Lo, their children.

Some were by themselves, alone, some in a tender embrace, others seemed almost alienated from one another. They were illuminated reverently by spotlights, in which they seemed confused and lost, even blind, I thought. They reminded me in this way of a man I had seen one evening peering strenuously out of his brightly-lit apartment, cupping his hands to his eyes, trying to make out the street below. All the passers-by, including myself, could see him illuminated perfectly in his light-box of a room, but he, surrounded by light, was completely blind to everything outside his little world. Each sculpture seemed also alone on its own plinth, what Murray described to me as “awkward, isolated islands”. Most of these animals look upward, in anticipation for something to soon arrive, happen, give clarity.

In a John Ashbery poem from 1956 the poet writes: ‘soon / we may touch, love, explain’ – a line, which has stayed with me and its relevance has changed with time. For example during the pandemic its meaning changed to incorporate my longing for those commonplace things then removed from us, a period when something as simple as touch became taboo. Murray’s sculptures too, created in isolation, express this anticipatory anxiety of the pandemic. And like Ashbery’s line, the meaning of the sculptures have broadened as time progresses. For example with the war in Ukraine having broken out since the exhibiting of these sculptures, they have incorporated into their expression of loss and separation the connotations of the refugee crisis. Images of mothers torn from children, families huddled in shelters or in camps, all this seems now to be silently preserved in these bronze creatures.

I think this ability for art to outgrow the moment it was made into, is to exemplify total contemporaneity. The contemporary is mistakenly thought of as a ‘now’, but in fact to be contemporary is always a temporal disjunction. It is a dislocation from time, not an obsession with the new. To be contemporary means to hover just above the things happening, drawn to the present but only bearing witness to it, always about to come into being soon but not just yet. The titles of The Limbo Sculptures seem to speak towards this: ‘Witness’, ‘Tether’, ‘Pause’, ‘Loom’ etc. The gentle humour of these creatures, their almost smiles, their forms and postures are folded with fear, worry, sadness; but perhaps there is also a calm acceptance of contradiction and turmoil as though they were floating stilly, as Keats says, ‘about that melancholy storm.’

The apparent ‘blindness’ of the sculptures seems related to the experience of living through an event that has ‘not-yet’ taken place but is still emerging into being. There was especially in the beginning of the pandemic a perpetual feeling that something had happened or was about to happen, but no one could say where or in what manner because it only ever revealed itself to us as its symptoms: the actual virus, microscopic, invisible, travels in obscurity. We only ever saw the symptoms of its being. We experienced the pandemic as non-real, non-actual, like an unbelievable subplot that goes off on a tangent and derails the legitimacy of the novel completely. But the pandemic was also hyper-real, beyond real, fulfilling cringe-worthy cartoon realities of apocalyptic computer games and sci-fi films. The ‘soon’ of the pandemic, the soon-it-will-end, soon-we-may-touch, was also a desire for the stable authenticity of the past. Every one of us constructed, fabricated an ideal future in which our banal lives before the pandemic were imagined as halcyon days to be recaptured. Though we knew this was not possible, the past lay over our eyes like scales obstructing our ability to see the present.

The name of Murray’s exhibition, Limbo, gives the sculptures the same irrealis mood of the pandemic. Limbo is a non-actual and liminal place, the inhabitants of which, frozen outside of time, await, indefinitely for the coming of Christ who will redeem them. They are caught inside of a ‘soon’ or a ‘not-yet’, which is the same untimeliness that post-colonial theorist Dipesh Chakrabarty called ‘the waiting room of history’. In this way the perpetual labour of tracing the folded child opens up into an allegory for contemporary South Africa (post-apartheid/post-Zuma), for the the pandemic, and even, as new catastrophe’s mount, of Ukraine, and of the demolished, dying earth. The sculptures are quiet, not revolutionary, they advocate nothing new, even the idea of ‘newness’, they seem to say, is an old worn out trope, another ruin for tourism. The creatures only gaze mutely in the direction of the ruins, that is both the way forward and the way back to childhood.

Arriving in London, from lack of money, I spent most days in bed listening to a crow bark over the terraces, the whisper of time in the draping leaves, bird songs smudged by the wind. I scraped my rent together piecemeal through various haphazard jobs which made my days feel blurred and frantic. I fell in love with a beautiful girl from Hungary who lived in an old run-down sweet factory in Limehouse near the Thames. And it was from there that I took the underground, in a marble coloured fog, to Chelsea, to see Brett Murray’s exhibition. And so the devastation of heartache and longing tinted my experience of the work.

Heartbreak, according to Barthes, renders the world thunderstruck: “various objects – whose familiarity usually comforts me – the gray roofs, the noises of the city, everything seems inert to me, cut off, thunderstruck like a waste planet.” Murray’s work is so familiar to me. And yet, seeing the small creatures in a gallery space in London, the opposite of South Africa in so many ways, is experienced by me as a disreality. I find it distressing, to be in the unfamiliar landscape, made aware of an unredeemable past presented to me by these artworks. A sculpture of two donkeys called ‘Tether’, isolated from the world in their embrace, both look up as if they have just heard the first crack of thunder.

Writing now, from a few notes and memories, Brett Murray’s small sculptured creatures reveal to me something of my state of mind at that time. Lost and frantic, identifying with the émigré protagonists of the novels I was reading, it seems to me now that I was living in a kind of mist. I can only describe this as a fugue state in which my previous life, my previous self, lived only in my memory, which seemed totally unreliable. Fugue from fugere means ‘to flee’: a fugitive from love, from childhood, and from home. The small, child-like sculptures, so intimate and anxious, made from the same eye, the same hand, as those objects of Murray’s that hang in my parent’s home so very many kilometers away, where I used to sleep to the sound of the ocean in the distance, felt like ghosts of the past. The colours of these sculptures, their earthy, soft patinas, were representative of the landscape of that home, the colours of the dry soil that the protea emerges from, the rocks and caves damp from mountain springs, the fynbos scorched by seasonal fires. Beset by memories and history, they reminded me of the mushrooms in Derek Mahon’s famous poem, who beg us to remember them, the lost people of Pompei and Treblinka. Under scrutiny, these memories, my own and the entire terrible history of South Africa, seemed increasingly fictitious, like I had created them myself. Rather than comforting me, the deteriorating memories now represented by these small, wide-eyed creatures threatened to derail my entire sense of self.

Looking at the child-like forms I wondered about Brett Murray’s own childhood, if his love for comics and cartoons had inspired the stylisation of these forms. So I fabricated in my mind an image of a young boy-Brett watching cartoons on a television set. On the screen he sees the hilarious violence of cartoons: Bugs Bunny blown up with dynamite, Mickey Mouse hit over the head with a baseball bat. They seem indestructible and plastic because one can revive them after immeasurable damage, unscathed in a second. Then again, TV was only available in South Africa in the late ‘70s, and Murray would have been a teenager. So perhaps the young boy is not watching cartoons but reading comics, in short-pants, cross-legged on a carpeted floor, his elbows on his knees, his head supported by his hands, his eyes as big as moons on his face. This boy we could imagine would be too young to consciously understand the immensity of what would be taking place in South Africa. But perhaps it operates in other ways, indirectly, on his psyche. A cartoon doesn’t represent in a direct manner either; it is by nature an unrealistic illustration.

We could imagine this young Brett’s quickening heartbeat, as something below his conscious thought connects the absurdity of these cartoons and their violence, with the scenarios of everyday life in the pristine, white’s paradise of South Africa. The violence of the manicured lawns and clean, ‘crimeless’ cities where the oppressed majority of the country is barely present.It seems to me that something about the violence of cartoons is integral to Murray’s practice and so demands some kind of theoretical attention.

Firstly, what is a Bart Simpson? What for example is at play in a character who is yellow, who has four fingers and whose hair is not distinguishable from his cylinder head? What are its constitutive parts? What makes a cartoon? and what kind of movement is the move of a cartoonist’s hand toward exaggeration, hyperbole and reduction? In the cartoon world everything is stripped to a grotesque surface essentialism. It says, ‘this is unequivocally the nature of this’: Mickey Mouse epitomises a mouse more than the actual rodents we occasionally catch a glimpse of behind skips and bins. Although in a sense this ‘glimpse’ is what the cartoon recognises as the real, this is what it captures and exploits. If we catch a glimpse of someone who steals a handbag, for example, and are asked to describe their features, we say it was a man, he had a balding pate, small eyes, a wooden leg – the police cartoonist renders us this image of the glimpse. This is the move of the cartoonist, always towards an abridgement, a best-of-compilation which eclipses the real thing.

In this sense the glimpse is something essential, a physical determination, a reduction of being to a singular physical aspect: strange head, big nose, no chin. In this sense it shares a constitutive similarity to the bad selfie. An unsuccessful selfie is one that is unused, unposted, deleted, the reasons for its discardment are based on a criteria of aesthetics one associates to oneself: this is my good side, I look best in this pose, the camera at this angle. So, implied in this aesthetic evaluation is an imaged understanding of the self. We tend to believe we know what our selves look like. The bad selfie is repulsive, because it shows us how we are seen beyond this image repertoire.

Isn’t this related exactly to the timely capture of the glimpse, isn’t this the move of the cartoonist’s hand? A move that is always an ontographical reduction to the essence as manifested in physical appearance. The cartoon, like the exoskeleton of an insect, is a complete externalisation. There is nothing elliptical, no psychology. The outrage caused by ‘The Spear’ was the outrage of reducing the president to a penis, to an image of himself beyond that which he projects. It is this forced reduction to crude physicality that makes the cartoon so ridiculous, absurd, exaggerated, and cutting: there is a subversive power in reduction. We fear cartoons, as we know they can reveal our greatest fears to us, that we are not the projected sample selves we present ourselves as.